Blog

Book Reviews

February 12, 2025

Book Review - Historical Perspectives on Smell by Jonathan Reinarz

The book's strength lies in its meticulous research and its ability to weave together diverse strands of historical inquiry, including social history, medical history, cultural studies, and even li...

Read More

Book Reviews

January 09, 2025

Book Review - Magical Aromatherapy, by Scott Cunningham

I am reading book called Mind Magic by Dr James R. Doty. It is such an empowering book which helps us to understand the science behind the power of manifestation by examining our mindset. He delves...

Read More

December 05, 2024

2025 Webinars, Masterclasses & Events

I'm so excited to share the exciting lineup of masterclasses and webinars for 2025.

With global mental health challenges on the rise, aromatherapy has never been more crucial. I'm passionate about ...

Read More

November 20, 2024

Sal’s 2024 Word of the year and essential oil of the year

The Collin’s Dictionary has chosen ‘brat’ as their word of the year. The word is characterized by a confident, independent attitude. While the word may have traditionally referred to a misbehaving ...

Read More

Book Reviews

October 25, 2024

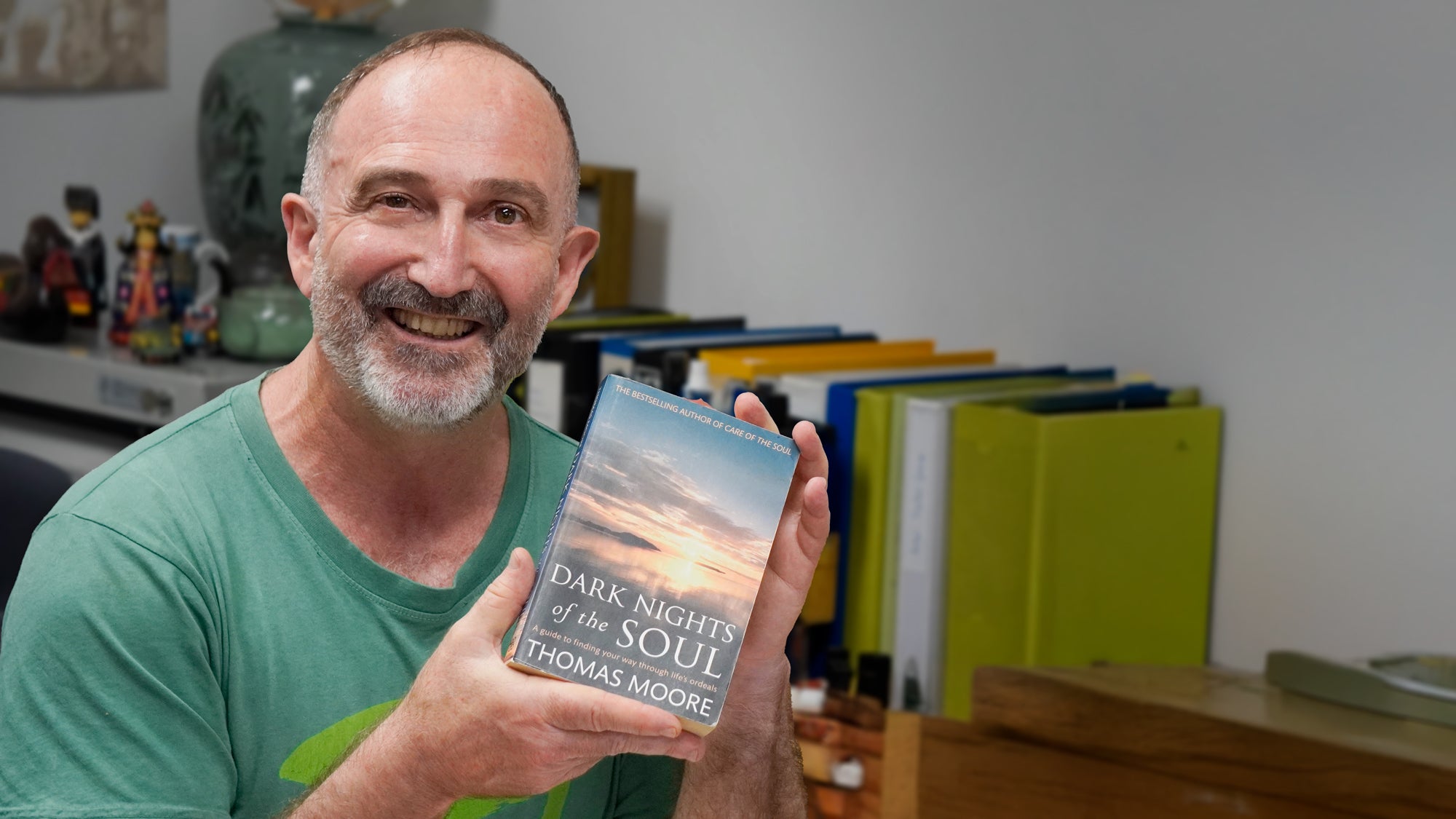

Dark Nights of the Soul – a guide to finding your way through life’s ordeals, By Thomas Moore.

I discovered Thomas Moore in the midst of the pandemic lockdowns. I found his books profoundly inspiring and compassionate. Dark Nights of the Soul and his highly acclaimed best seller Care of the ...

Read More

Blending Tips

August 27, 2024

The Scent of a Unicorn

The unicorn is a symbol of purity, magic, innocence and power. The unicorn is the most magical of all the mythical animals. The unicorn is often depicted as a pristine white creature, representing...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

My 2023 Word and Essential Oil of the Year

My word of the year is ‘transilience’, a trait we all need, in order to navigate these uncertain and volatile times. There is no need to remind you of the ever-growing list of uncertainties such as...

Read More

Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

Aromatherapy – bridging lifestyle medicine and functional medicine

I have been asked to speak to a group of undergraduate doctors in their final year of study about aromatherapy. I am both ecstatic and honoured to share my passion for aromatherapy with a group of ...

Read More

Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

The 2022 Essential Oil of the Year

I was reading about permaculture so that I could improve my gardening skills, so I was therefore excited to see a Guardian article announcing that the word of the year was ‘permacrisis’. What immed...

Read More

Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

The Wounded Healer and Aromatherapy

The wounded healer archetype has its origins in Greek mythology and shamanic traditions. Images of the wounded healer permeate religion, philosophy, and art and are now used in psychotherapy, couns...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

Boosting the Immune System?

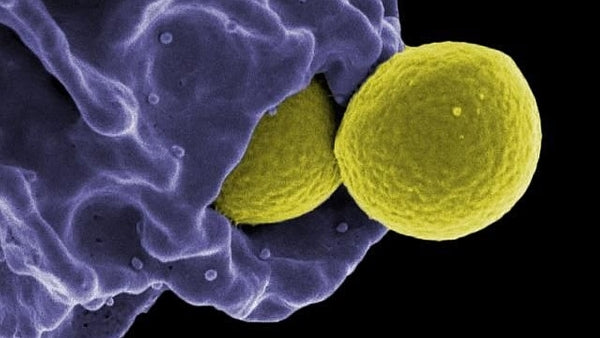

The complexity of the immune system is considered secondary only to that of the nervous system.The immune system is classified in two broad categories. The innate immune system (non-specific immune...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

Terrain or Germ Theory?

In the chapter on immunity in the second edition of The Complete Guide to Aromatherapy, I introduced the important role of microbes.1

Read More

Education

April 26, 2024

My upcoming webinars on ways to support the immune system

In Chapter 32 – The Immune System of the second edition of The Complete Guide to Aromatherapy, I introduced the role of microbes by quoting Simon Mills, internationally acclaimed herbal medicine pr...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

Indian Sandalwood Oil in Skincare

In traditional aromatherapy, Indian sandalwood, Santalum album, is commonly used in skincare for dry and sensitive skin. The oil is soothing and cooling, and reputed to have anti-inflammatory activ...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

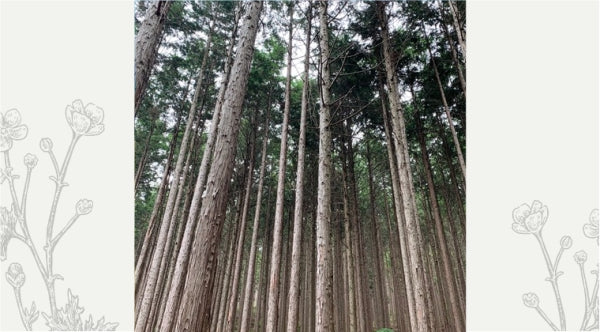

Shinrin-yoku Interviews in Japan

For my Aromatherapy & Shinrin-yoku Webinar, I had originally intended to go to Japan to take you on a tour of the distillery producing our Japanese pure essential oils.

Unfortunately, I was no...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

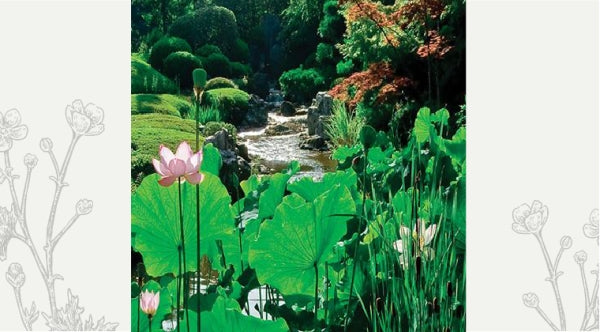

Aromatherapy and shinrin-yoku

What is shinrin-yoku?

Many cultures have long been aware of the unique relationship we have with nature.

In Japanese, shinrin-yoku is defined as ‘forest bathing’ or ‘taking in the forest atmosphere

Read More

Safety

April 26, 2024

Can I diffuse essential oils around cats?

Several years ago, I wrote a blog to dispel the concern that it is not safe to diffuse essential oils around cats. I did -and still- err on the cautious side by recommending that it is not a good i...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

Are essential oils sustainable?

Personally, I think it is unfair that she has singled out ‘aromatherapy’ and those businesses associated with ‘new age’ movement, as her criticisms are relevant to so many corporations that are inv...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

How Australia is creating a long-term sustainable future for one of the world’s most precious essential oils - sandalwood.

Excessive harvesting of sandalwood trees from the wild without a strategy for replanting has substantially reduced the availability of sandalwood in India. This has resulted in global shortages and...

Read More

Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

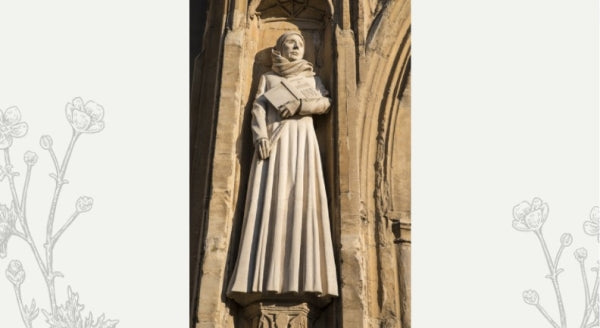

All Will Be Well - The Wisdom of Julian of Norwich and Aromatherapy

The 8th March was International Women’s Day (IWD) and this year’s campaign theme was #BreakTheBias.The official IWD website states that whether deliberate or unconscious, bias makes it difficult fo...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

Don’t worry be happy?

Perfect Potion’s Happy & Calm blend is such a beautiful and simple blend of sweet orange, lavender, Roman chamomile and frankincense. The warm, resiny aroma of frankincense comforts the soul an...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

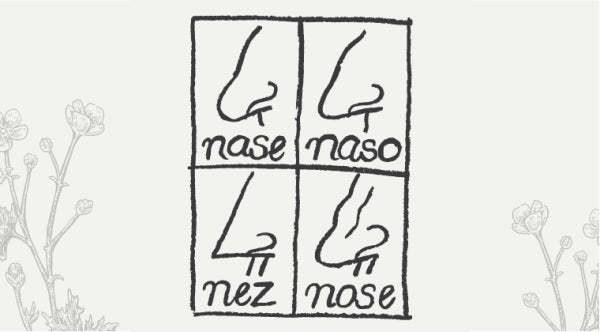

COVID-19, Aromatherapy and Anosmia – an update

In preparing for my first webinar for 2022, I have referred to the most up-to-date research – which is constantly being updated and revealing the true nature of COVID-19 related anosmia. Much of wh...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

Essential Oils to Flourish

I recently came across a very interesting paper exploring how stress and depression impair the immune system. Furthermore, the study found that emotional stress can weaken the body’s ability to dev...

Read More

General

April 26, 2024

Resilience

This morning I came across a beautiful heartfelt article in the Guardian by Chibundu Onuzo reflecting on the last two years of the pandemic, and how she has come to appreciate the character trait ...

Read More

General

April 26, 2024

Julian of Norwich

In the midst of the long-extended lockdowns that we were experiencing in most places in Australia, I did an online search which involved the words - pandemics, mental health and spirituality. At th...

Read More

Education

April 26, 2024

Essential oil of the year

Many of us have had to deal with the ongoing challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic; associated with COVID infections, lockdowns, travel restrictions and disruption to our normal life. I was hoping th...

Read More

Education

April 26, 2024

My 2022 Free Aromatherapy Webinars

I am so excited to announce the topics and the dates for my 2022 webinars. These webinars will go for approximately 45 minutes and will be free of charge. Please click the links for each webinar fo...

Read More

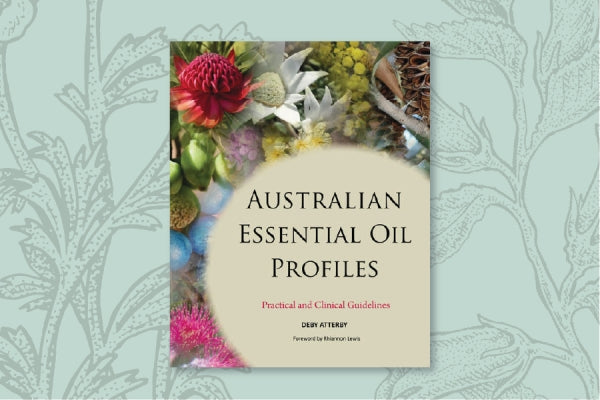

Book Reviews

April 26, 2024

Australian Essential Oil Profiles

By Deby AtterbyPublished: 2021Pages 359

Australia is blessed to be home to a diverse range of aromatic plants, from which some unique and very potent essential oils are produced.

In 2000 I was so ...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

COVID-19 and Anosmia

A recent study reported that one in five people who experienced smell loss as a result of COVID-19 reported that their sense of smell had not returned to normal eight weeks after falling ill. The r...

Read More

General

April 26, 2024

To Flourish

I have always been passionate about aromatherapy as it allows me to flourish; however, what does it mean to flourish?For example, this year we have just established an aromatic garden and it is so ...

Read More

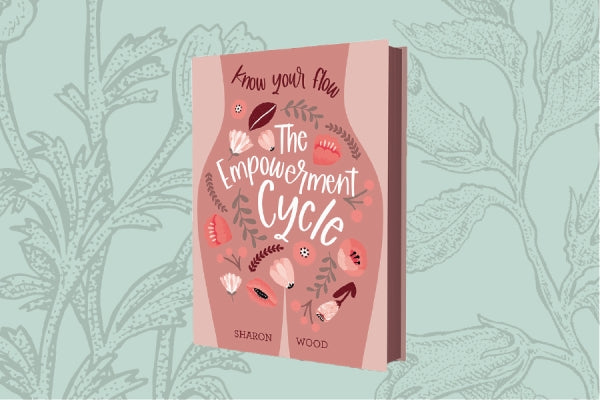

Book Reviews

April 26, 2024

The Empowerment Cycle

Aromatherapist, educator and author Sharon Wood has done an amazing job continuing the legacy she began many years ago when she created Emgoddess.

Read More

Education

April 26, 2024

Aromatherapy & Mindfulness. Interview with Matsuyama-san

In preparing for my Aromatherapy and Mindfulness Masterclass earlier this year, I had the honour and privilege of interviewing highly-esteemed Rev. Daiko Matsuyama: deputy head priest at Taizo-in...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

The role of the gut microbiota and immune responses to vaccination

A 2021 report published in Nature Reviews examines the role of the gut microbiota in modulating immune responses to vaccination

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

The Pandemic, Fear, Hope and Resilience

In preparing for my next masterclass, Aromatherapy and Mental Health, I began researching the impact of the pandemic on mental health. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health has been ...

Read More

Essential Oils

April 26, 2024

World Gratitude Day

Today is World Gratitude Day. It is wonderful that a day has been dedicated to gratitude. Today, and I hope every day, we can find reasons to express our gratitude. Researchers have now identified ...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

Plant-based diets, pescatarian diets and the severity of COVID-19 symptoms

While several studies have indicated that healthy dietary patterns may play a role in improving the immune response, this was the first study to examine the association between dietary patterns and...

Read More

Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

Art of Blending Masterclass

Somehow, I knew I was destined to be involved in a life involving scent. Ever since I was a young child I would often sneak into my parent’s room and privately indulge in my mum’s alluring collecti...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

I just had my second jab

I need to start this blog by disclosing that I have just received my second AstraZeneca jab, and to be honest, I am now feeling very relieved. I hope that as more vaccines become readily available ...

Read More

Health & Wellbeing

April 26, 2024

Our role as holistic therapists during the pandemic

The editorial of the Winter 2021 edition of The Australian Journal of Herbal and Naturopathic Medicine by Susan Arentz states that, like other health professionals, naturopaths and herbalists are i...

Read More

General

April 26, 2024

Mother Earth – creating harmony with nature

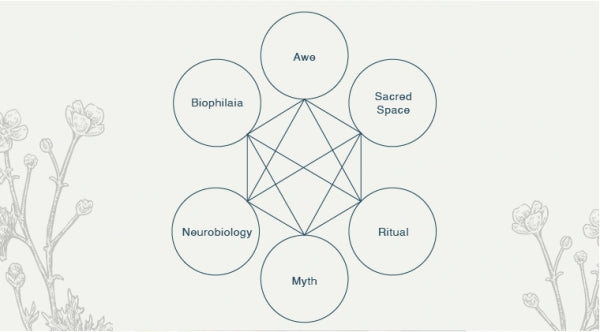

The concept of biophilia suggests humankind is shaped both cognitively and emotionally through the interactions with nature. However, the prevailing view held by many Western societies is that huma...

Read More

Subtle Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

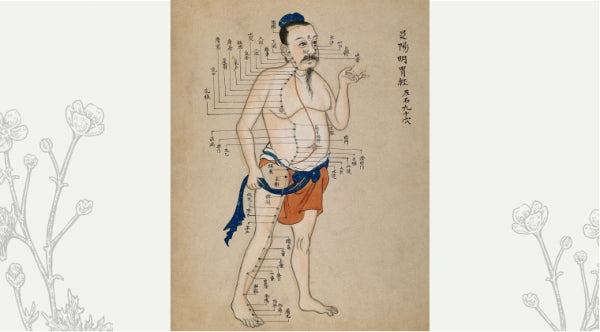

Psyche & Subtle PART FOUR: Biofield Therapies and TCM

In the second edition the title was Subtle Therapies. The change to Biofield Therapies has disappointed several individuals, so please allow me to explain why I decided to change the title of the ...

Read More

Subtle Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

Psyche & Subtle PART THREE: The Spiritual Dimension of Scent

Today we explore Chapter four - the spiritual dimension of scent of my new Volume III of The Complete Guide to Aromatherapy.

Many aromatherapists acknowledge the effect of scent on our psyche. W...

Read More

Subtle Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

The Psyche & Subtle PART TWO: Sacred Scents

At the 2018 NAHA conference I spoke of The role of scent in culture and spiritual practices, and how this has helped establish a framework for the practice of aromatherapy. In preparing for this p...

Read More

General

April 26, 2024

My Kokoro Is Sad

This is the most difficult message I have ever had to write. I was hoping time would heal, but sometimes it cannot. My kokoro is sad. Kokoro, by the way, is a beautiful Japanese word relating to th...

Read More

Book Reviews

April 26, 2024

The Enlightened Mr Parkinson: A Book Review

I was fascinated and intrigued and wanted to learn more about this incredible person. I love reading historical biographies that document the history of medicine, and the 18th century was indeed an...

Read More

General

April 26, 2024

Indigenous rights and cultural appropriation

One of the very important issues that Thayer addresses in her thesis, The Adoption of Shamanic Healing into the Biomedical Health Care System in the United States, is the appropriation of indigenou...

Read More

Aromatherapy

April 26, 2024

The scent of nostalgia

Scent is like music to the sense of smell; evoking emotions, memories and imagery. It is the most abstract of the senses: we are often lost for words when trying to describe a particular scent. At...

Read More

Blending Tips

April 26, 2024

Blends with Thyme Oil

Create your own Blends - Thyme oil has been referred to as one of the most important essential oils in aromatherapy. It is always important to be aware of the chemotype being used. I have been meti...

Read More